When I was kid I wasn’t exactly sure where home was. I knew I was American, but I also knew that my parents had taken a job overseas so I had been born and raised as an expat in Saudi Arabia - a place that shaped me but did not claim me. Many of my peers could tell a similar story; we could rattle off the various countries we had lived in, but our sense of belonging was tethered more to temporary assignments than to ancestry. We were what is known as “third-culture kids,” which meant we were adaptable to anywhere, but deeply rooted nowhere. We were taught this was a strength because in a world moving rapidly toward globalization, we were already a step ahead.

But as I entered adulthood, the virtues I’d been taught to cultivate began to feel like liabilities. I couldn’t answer basic questions like where are you from? without spiraling into abstractions. Meanwhile, some of my third-culture peers began to speak of a persistent ache of disconnection, which is a well-documented experience in the psychological literature on third-culture kids.

Over time, I noticed something curious. The same language that had filled my childhood was being echoed in mainstream American discourse; detachment to place and heritage was increasingly upheld as an enlightened ideal, while patriotism and a desire for a cohesive culture became dangerous ignorance. At the same time, the American population was increasingly mobile, with people drifting from city to city as communities thinned out and families scattered. Psychologists began reporting a growing epidemic of loneliness and despair.

I realized that the ideology that had shaped my life as a third-culture kid was being imposed on the American people as a whole; an entire nation had lost its sense of home and its people were living like expatriates, even those of us who had never left.

How had this happened? Well, it wasn’t an accident.

The Gaslighting of a Civilization

Following the Second World War, a growing class of intellectuals, technocrats, and cultural architects, began to view traditional Western life as a breeding ground of authoritarianism. The family home, with its roles, rituals, and inherited traditions, came to be seen as a hotbed of repression, while a strong national identity was seen as a dangerous precursor to fascism. The solution was to engineer a total transformation of the age-old understanding of home, belonging, and identity.

To some, it may sound like a conspiracy theory to claim that the West’s own leaders set out to sever people from their roots, but this is not speculation, it is historical fact. Intellectuals such as Wilhelm Reich and others associated with the Frankfurt school believed that traditional Western values were the foundations of repression and potential authoritarianism. Many of these European thinkers were welcomed into elite universities in America, where their ideas took root.

Over the following decades, their worldview seeped into the American education system, media, and government bureaucracy, shaping generations of policymakers, journalists, and teachers. What began as a fringe theory became a dominant intellectual framework of the postwar West. Most adherents weren’t consciously plotting to dismantle Western society, they simply believed as they had been taught – that the highest form of educated life was to transcend the old-fashioned relics of humanity’s past, like tradition, religion, and national identity. This way of thinking elevates rootlessness and hyper-individualism into elite cultural ideals, giving us the aspirational image of the modern person free from backward tradition, while people who maintained their traditional values are sneered at as uncouth yokels.

Over time, institutions and leaders began to dismantle the idea of home altogether by undermining everything that gives home its meaning. President Biden dismissed the idea of the American “melting pot” as outdated, championing instead a society comprised of fragmented cultures. The Smithsonian Museum reframed American values like hard work and the nuclear family as expressions of “toxic whiteness.” The Department of Homeland Security went so far as to flag expressions of patriotism or nostalgia as potential extremism. In Britain, Prime Minister Gordon Brown redefined Britishness as nothing more than a shared set of values, severed from heritage, while the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, declared London a “global city,” unmoored from historic cultural identity.

In this way, a suffocating cultural message reached critical mass: home is not something you love or protect, but something you must interrogate, deconstruct, and ultimately outgrow.

The Colonized

It is ironic that people in Western countries have spent years immersed in the rhetoric of decolonization, without recognizing that the process of colonization has been carried out against them. As N.S. Lyons has written, just as in classic colonial regimes, Western populations have found their national self-determination eroded in favor of supranational rule by elites who see the native population as ignorant and in need of reeducation.

Following the classic pattern of colonial interference, distinct cultural identities are forcibly broken down, internal divisions stoked, and historical memory severed through censorship, propaganda, and school-based indoctrination that teaches students that their heritage is uniquely oppressive and shameful. While other civilizations have drawn strength from their past, under this new order, the West’s past was framed as an ignominious shame, little more than a chronicle of oppression, theft, and brutality. This, despite the fact that the West is not unique in its sins, as violence, conquest, and inequality are the common inheritance of every civilization. The West is, however, unique in its virtues, like the cultivation of equality before the law, pluralism, and a capacity for self-critique and reform.

Meanwhile, America’s long-standing immigration framework was overturned. For most of America’s history, immigration was limited, gradual, and focused on European populations that would assimilate into the existing Anglo-American framework. But in the 1960s, immigration was reframed as a moral imperative rather than a tool to benefit the nation, while the idea of assimilation was replaced with a celebration of multiculturalism and the myth of the “propositional nation.”

As the years went by, immigration accelerated to historically unprecedented levels, despite the opposition of the public, leading to depressed wages, increased crime, overwhelmed social services, and the further erosion of any coherent sense of cultural identity. Immigration, which can be a good thing when done right, was turned into a catalyst of disorder. The speed and scale of this immigration rapidly transformed communities, making the local feel foreign so that people began to feel like expatriates in their own homeland. Yet when the public voiced their discontent, they were met with censorship and condemnation. This loss of home was not only permitted, it was mandated, and to grieve the loss is seen as a moral failing.

The Colonizers

The postwar effort to dismantle the cultural structures seen as precursors to fascism – family, tradition, patriotism – conveniently dovetailed with the economic needs of an emerging mass economy that required standardized consumers. Because of industrialization, goods could be produced on a massive scale. To make that scale profitable, there had to be a matching level of demand: people had to be made to want the same things, which meant reshaping their tastes, habits, even their sense of identity. The more uniform the population became, the more efficiently mass-produced goods could be sold to them.

Rooted people became a problem because rooted people don’t scale. Deep ties to community, place, and tradition, slowed down the development of mass systems, creating friction for the smooth operation of global markets and bureaucratic governments. As Auron Macintyre writes, you cannot extract the endless growth required by liberalism from communities that want to stay small and self-sufficient.

For all its celebration of “diversity,” the Western establishment is, in practice, very hostile to the real thing. True diversity arises from distinct local cultures and rooted traditions, and is therefore incompatible with centralized control, meaning it must be dissolved. In its place we get a hollow substitute: a curated display of diverse skin tons, pronouns, and foreign flags – that affirm the same slogans, desire the same products, and submit to the same system. It isn’t diversity at all, but uniformity in disguise. Cosmopolitanism served as the ideological justification for this transformation; if people could be convinced that belonging was backward and tradition was dangerous, they would not resist the breakdown of their communities, they would welcome it as high-status progress.

And so we have been taught to be suspicious of the very things that once gave life coherence: faith, family, inheritance, place. We drift through placeless cities, work in jobs with no connection to our communities or neighbors, and raise children in systems that treat our history as something dangerous to unlearn. We struggle to form connections, to keep traditions alive, to even name what’s missing because we’ve been trained not to see it.

This is how Western man became the third-culture man, uprooted not by exile but by design, and why so many of us now live as expatriates in our own homelands.

And yet the need for home has not gone away. Forcibly repressed, it resurfaces in disordered ways, like consumerism, identity cults, and movements that promise some fantasy of return. Because if you deny people a real home, they will seek fake ones and cling to anything that offers even a shadow of belonging. The cost of this disorder is everywhere: the collapse of fertility, the epidemic of loneliness, the record rates of suicide, depression, and addiction as people succumb to a kind of spiritual suffocation, robbed of one of the most foundational aspects of a well-ordered human life.

Rehoming the Imagination

Having spent most of my life as an American expatriate, I find myself trying to imagine how this journey ends – how I might one day return, not just physically, but in spirit, to the nation of my forebears. I wonder what it will mean to belong again, to reclaim a sense of home that was always quietly calling. What I’m wrestling with as an individual is what we are all now being asked to confront on a civilizational scale: how to reconcile our inheritance as Americans and how to begin, however imperfectly, the long return.

I was raised to believe in the concept of being a “global citizen,” but I now recognize that was never possible. As Wendell Berry writes, “One cannot live in the world; that is, one cannot become, in the easy, generalizing sense with which the phrase is commonly used, a ‘world citizen.’ There can be no such thing as a ‘global village.’ No matter how much one may love the world as a whole, one can live fully in it only by living responsibly in some small part of it.”

The first step toward living responsibly in our own small part of the world begins with imagination: we need to imagine, once again, what home means. To feel it as good, to speak of it as sacred, and to remember that we are not just shoppers in a global mall, we are born from people, placed in time, bound by memory and love. We must decolonize our own minds from any belief system that tells us that home is a dangerous concept. Wanting a home is not treacherous and it is not wrong; it is as fundamentally human as wanting food to eat and air to breath.

The beauty of this imaginative work is that it begins to restore us almost immediately. We are currently spending enormous psychological effort pretending like we don’t need home, convincing ourselves that it isn’t existentially taxing to be rootless, to have no community, to permit the constant denigration of our ancestors and history. But this posture is not natural; it requires continuous maintenance. The moment we let go, even just a little, something ancient and good rushes in.

Rehoming the imagination must start with our inner worlds, but it will not end there. This moral restoration will naturally be accompanied by tangible action. We can buy local, recover family traditions, get to know our neighbors, serve our community, join local institutions, and learn the history of where we live and how our people fit into it. We can recognize and celebrate the tremendous efforts of our ancestors to build something lasting and good, and refuse to apologize for who we are or for loving where - and who - we are from. Ultimately, we must reject the lie that we are nothing more than consumers of identity, just free-floating individuals detached from land and lineage, and acknowledge that home is a real thing that is built, inherited, and loved.

The longing for home is not a flaw to be overcome, it is a compass pointing us back to wholeness. A moral imagination of home sees limits as sacred. It knows that to be human is to be placed - not just anywhere, but somewhere. In flesh, in time, in memory. And if we are to endure, if the West is to endure, we must find the courage to imagine it again.

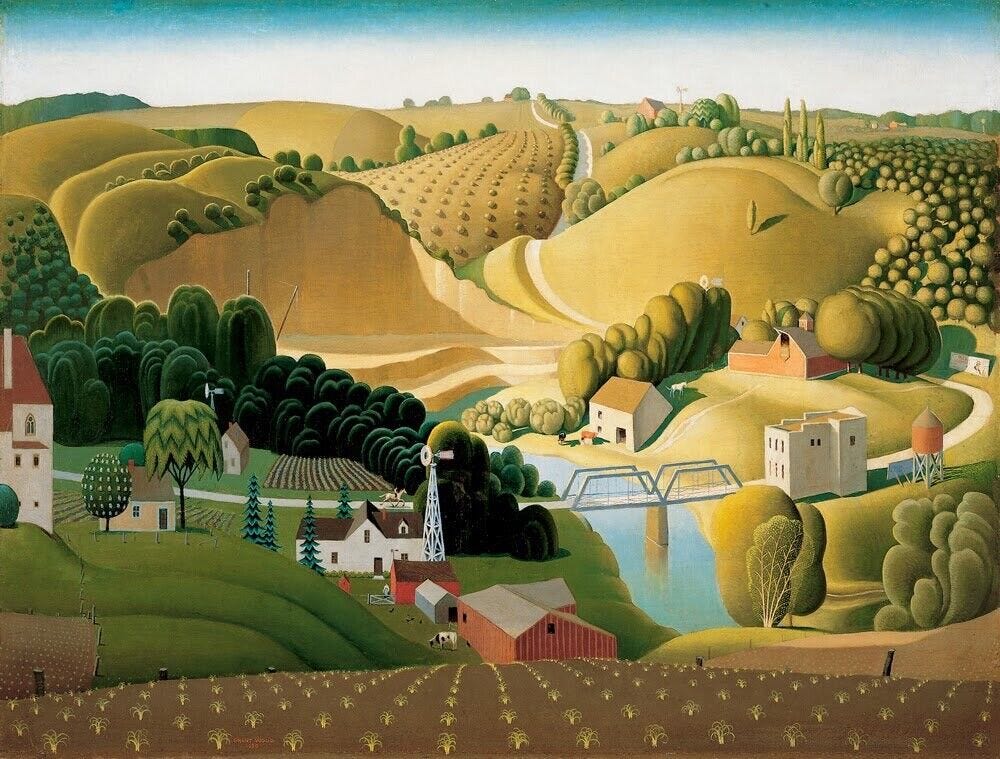

Paintings:

Stone City, Iowa by Grant Wood

The Veteran in a New Field by Winslow Homer

Snap the Whip by Winslow Homer

The Old Stagecoach by Eastman Johnson