We walk through the Khobar souq.

Dress Land, Bombay Fashion, Madina Restaurant, Fresh Fish Center, Golden Juice, the shop signs beckon in Arabic, Urdu, and Hindi. In the midst of the crowd, I spot a father walking with his three small daughters, each in a saffron yellow shalwar kameez. Two boys on a bike, one pedaling, the other standing on the struts, weave in and out of traffic, hollering at everyone they see.

We enter a leather goods shop where rows of hand-tooled sandals sweep up the walls to the ceiling and a cobbler sits cross-legged in the corner, surrounded by his tools and bits of leather. He introduces himself before dashing across the street to a cafe, returning with three paper cups of steaming chai.

While we sip the tea, he works a stiff thread through the sole of a shoe and tells us that he left his home in Peshawar 25 years ago and has been working in Khobar ever since. When he arrived, he says, the buildings were shorter and there wasn’t as much traffic. He tells us that sometimes he forgets it is the same city that he remembers from his youth. As we talk, men filter in and out of the store, bringing belts and wallets in need of repair.

We make our purchase and step back into the night.

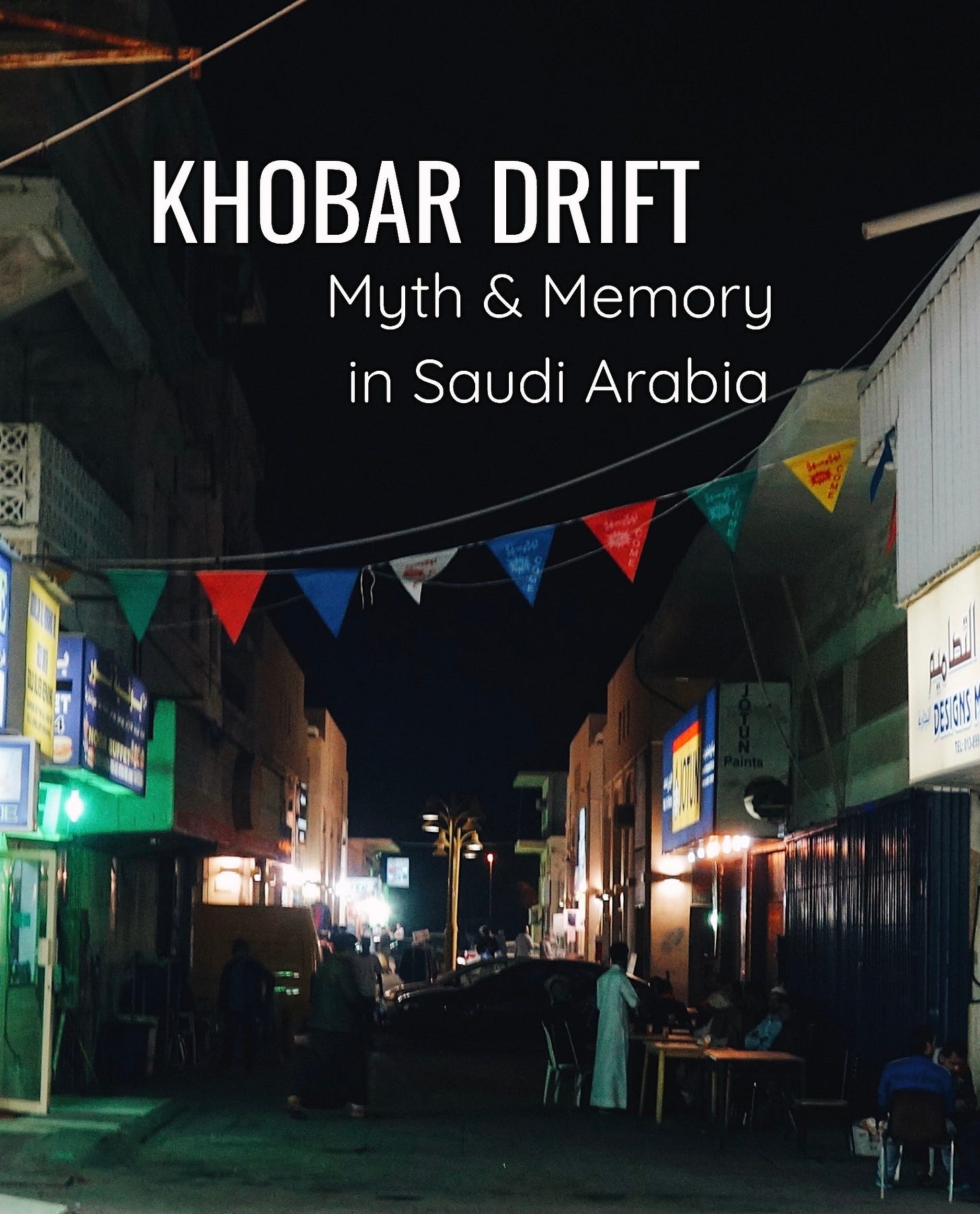

In 1938 oil was discovered in commercial quantities in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and Khobar began its evolution from a small fishing hamlet into a hub of commerce and industry. But behind today’s busy sprawl of international chain stores and fast food restaurants, the shadowy alleys of Khobar’s souq remain dense with strangeness. These disheveled lanes are the sight of my most potent childhood memories and for weeks something has been tugging at me to make a pilgrimage along the ley lines of my youth.

People meander down the streets in small groups, enjoying the winter evening. It rained earlier and the excitement of this rare delight still shivers through the air. Children slip out of doorways, sandals slapping sharp rhythms against the sidewalk. A truck roars past and my abaya catches in its wake, flaring around my knees, and I spin in a circle, pushing it back down. On one corner, a group of men take up half the sidewalk playing a game of carrom, flicking the pieces with snapping fingers. We pass a shop plastered in fliers advertising shampoo and nuts, where dolls with sun-bleached faces fill the window.

Iain Sinclair has said that the solitary walker is followed by a ghostly contingent of other walkers who murmur in his ear, trying to tempt him down one path or another. For me, these whispering stalkers aren’t strangers but family members; these aren’t just the streets of my childhood, they are the streets of my parent’s childhood, as well.

We are American expatriates who call Saudi Arabia ‘home’.

My father grew up in a tiny town further up the coast and as a child he viewed Khobar as a booming metropolis. He and his family would take long, sweltering bus rides whenever they wanted to visit, but it was worth it to reach the city where everything happened first, fastest, and best. He recalls the steamy summer day he watched as one of the country’s first bulk refrigerators was installed, slipping into the shop afterward to marvel at the frigid air. And the day in 1960 when Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie came to town and my father saw him and King Saud sweep by with their gleaming military escort.

Growing up with these stories, and the stories of my mother and grandparents, makes for me a Khobar that exists in multiplicity with itself. Wherever I go, I’m never just in the Khobar of today, but in the Khobar of so many yesterdays, my vision dazzled by the manifold memories. Sometimes I think I know this city too well to ever experience it directly; instead, I traverse a gauzy assemblage of recollections, navigating on a level quite distinct from mundane topography.

Across the highway, into the other side of the souq, things are livelier and a tinge of sharp-elbowed fervor permeates the sidewalks. We pass Filipino bakeries and tailors, and every street corner is plastered with fliers advertising spare rooms – Roommate Wanted – Pinoy Only.

In front of a barbershop two men sit on the curb playing the fastest game of chess I’ve ever seen, their hands slapping the timer in a frenzied blur. A soft trickle of music seeps out from a tiny vegetable shop. I peek inside and find a wall-mounted TV showing shaky footage of some festival where men in bone-white thobes are dancing the ardah, Saudi Arabia’s traditional dance. These distant, dancing men sway from side to side to the insistent beat of a drum. The shopkeeper turns away from the TV to give me a grin, a stick of bristly miswak wedged between his teeth.

A soft rain begins to fall as we walk on and the street settles around us, like a bird quieting for the night.

And then, there it is: the shop we call the Time Warp Toy Store. Enter and it is 1983. He-Man still reigns supreme and Barbie has crimped hair and dangerously sharp shoulder pads. I pick up a puzzle in a cardboard box, on the side of the box a stamp reads: Made in West Germany.

The shop is owned by a handful of Yemeni brothers. As a child, a trip to the store was unfinished until one of the brothers, sitting in the plastic chair in the corner, laughed at the way you pestered your parents for whatever toy was that month’s necessity and gave you a piece of candy.

As an adult, my father once purchased a model airplane from the Time Warp Toy Store. When he paid, he laughingly told one of the brothers that when he first saw the toy, thirty years ago, it had only cost 4 riyals, whereas now the price was 24.

Without missing a beat the owner replied: “If you give me back those thirty years, I’ll give you back your twenty riyals.”

Through the dim and cluttered aisles we roam, unearthing treasures from decades past. Here is a kit so you can put together your very own Challenger Shuttle model. Here is Home Office Barbie, Astronaut Barbie, and Totally Hair Barbie. And here is a replica Patriot Missile launcher I would have loved to have when I was a child dragging my gas mask to and from school during the 1st Gulf War.

Eventually, we pay for our nostalgic purchases and step back outside where we find the soft rain has been replaced by a cloud of fog that coats the street in a watercolor haze.

Suddenly, I am overcome by the weight of a lifetime of memories, a heavy certitude of belonging that I tell myself must be what home feels like – even though, as an expat, I’ve always known I will one day have to leave. Somehow, this tenuousness has become an integral part of my sense of home and I exist in a constant state of perpetually refreshing nostalgia, missing things before I’ve even left.

We head to the corniche, stepping off the petunia-lined walkway and sinking into the soft white sand.

I am reminded of a folk story about a little Bedouin boy who left his family tent one night, despite being told not to by his parents. He sneaks away into the dunes because the wind sounds like someone calling his name. The boy never finds anyone and by the time he finally returns to his family’s tent, he discovers that decades have passed in his absence and his family is now changed beyond recognition. They don’t recognize him and will not accept him. The moral of the story: in your search for external fulfillment, don’t forget what is truly important - family, custom, and home.

But there is something else, something in the way that the boy returns. He comes home expecting to find everything as he left it and it might be that it is his shouts of anger and disbelief that disturb his family, for it is only after he has made a fuss that they cast him out. Maybe it is his refusal to accept the shifting reality of his world that condemns him to never find acceptance within it.

It is a lesson from the desert that I translate for these quickly changing streets – hold lightly to the warp and weft of reality, lest you be cast out. Accept the strangeness you find, even though it stings. Remember that just like us cities have their stories of self and it is up to us to navigate their swiftly shifting currents.

The need I’ve been feeling to revisit these old streets feels settled here on the beach, drowned out by the steady lapping of the waves and the inky smell of the water. Leaving the caul of memories to the city at our back, we drift away from the glow of streetlights and walk across the sand, toward the beckoning darkness and the black rolling sweep of incoming tide.

This essay, in its original form, was published by The Smart Set in 2017. It represents the first public installment of my psychogeographic writing, which continues to this day. To read more of my explorations on place and psyche in the Arabian Gulf, you can read my debut book Drifts.